March 19, 2024

One hundred years ago this year, a strain of influenza, or flu, hit the globe, leaving more than 500 million people afflicted by the flu worldwide.1 Without vaccines or antiviral medications, the 1918 flu pandemic, also known as the Spanish Flu, proved to be one of the most severe outbreaks in history. Now, a century later, medical and scientific advances have been made to treat the illness and prevent flu pandemics.

The First Known Outbreak of Flu

Spring 1918 – The Soldier Spread

Flu is a contagious disease that primarily impacts the respiratory system. There are four different types of flu viruses, though the more common ones are influenza A (found in humans, birds, and pigs) and influenza B (typically only found in humans). While flu may be fairly well known and understood today, 100 years ago, that wasn’t necessarily the case.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the average life expectancy for women in the mid-1910s was 54 years, while the life expectancy for men was only 48. Those life expectancy averages dropped by 12 years during the spring of 1918 when the first waves of influenza emerged in America at a Kansas military camp. Soldiers living in close quarters during training and wartime may have played a role in its outbreak, as sporadic flu activity spread unevenly throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia over the next six months while hundreds of thousands of soldiers were deployed for WWI overseas. They spread the disease amongst themselves and opposing forces, and then on to civilians in the towns they occupied.2 When compared to other pandemics, including the Black Plague in the 14th century, the 1918 flu pandemic was unique in how it spread, as armies carried it across the globe on foot and boat.3

Though dubbed the Spanish Flu because of how many Spaniards it was said to have claimed by 1918, researchers later thought it to be inaccurate, because the flu’s origins are now thought to have been in the United States. A century ago, flu symptoms were similar to today's flu – fever, respiratory symptoms including runny nose and sneezing, and nausea, diarrhea, and body aches. During the 1918 flu, though, additional symptoms included dark spots appearing on the cheeks, as well as an overall blue skin tone, as their lungs filled with fluid and they struggled to breathe.3

Fall 1918 – Peak Influenza

A second wave of the flu outbreak in the fall of 1918 prompted New York City’s Board of Health to add flu to the list of reportable diseases nationwide and required those with flu to be isolated at home or in the hospital. To make matters worse, the nursing shortage at the time meant that there weren't enough healthcare providers to care for those with the flu. This period was dubbed the second wave as its spread was seemingly at an all-time high, reaching all parts of the globe.

Winter 1918 – Stop the Spread of Flu

There was a distinct third wave of the flu that occurred during the winter of 1918 and carried on into the spring of 1919. It wasn’t as damaging as the second wave, as by that point, many diagnosed with the flu had either passed away or become immune. However, it didn’t taper off until summer of that year. In the winter of 1918, public health officials cautioned against coughing and sneezing and began issuing educational materials to curb the spread of the disease. This began a century-long journey to where we are today, with a number of organizations promoting the prevention and treatment of the flu.

Looking for an alternative version of the above infographic?

How to Solve a Problem Like the Flu

1930s – Viral vs. Bacterial Infections Are Distinguished

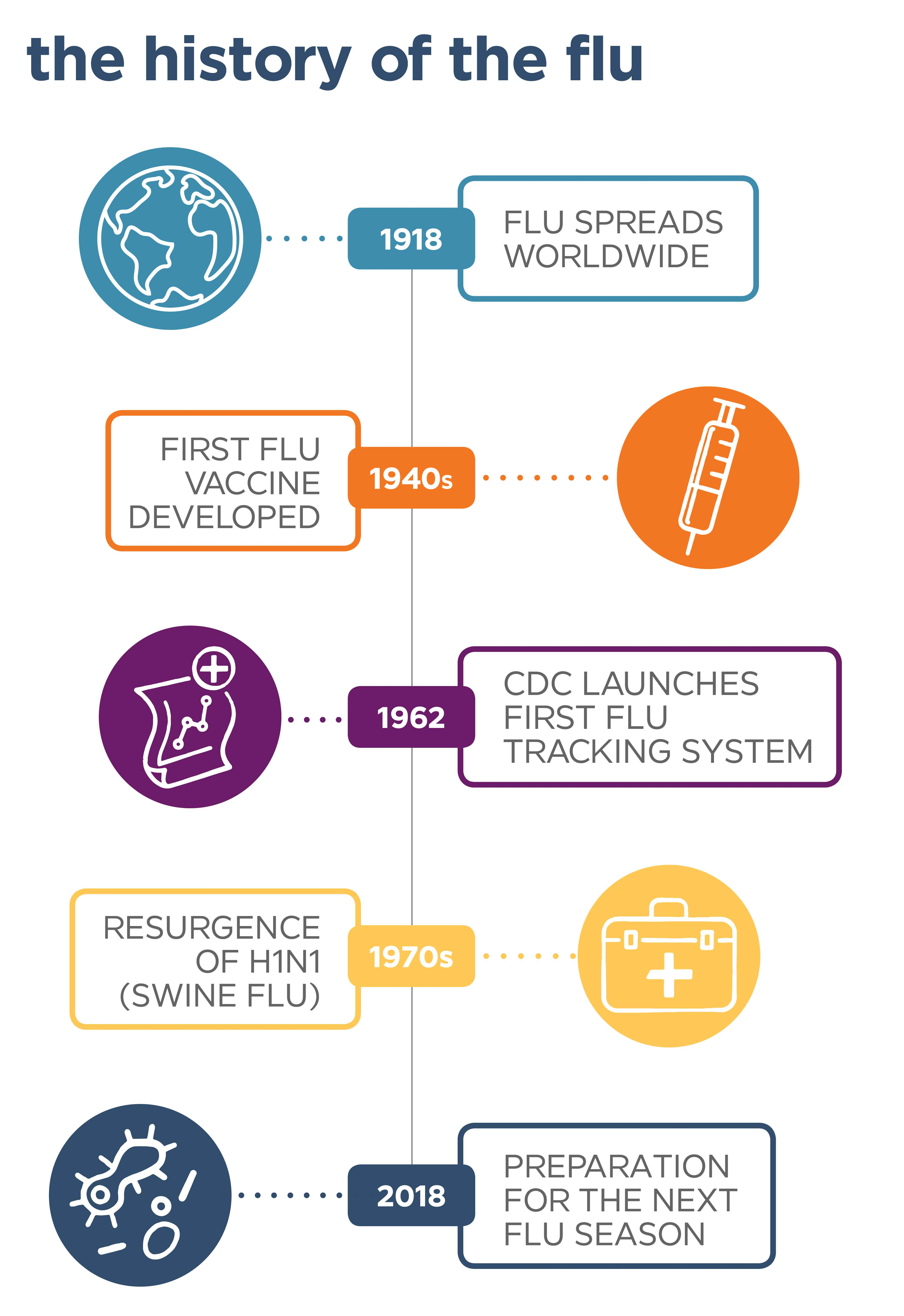

In the 1930s, scientists helped determine that influenza is caused by a virus, rather than bacteria. That means that antibiotics won’t treat the flu, as they’re meant to treat bacterial infections instead of viral infections. However, the flu can be treated with antivirals to help lessen flu symptoms and shorten the amount of time you’re sick.4 The next decade was spent discovering more about alternate strains and possible vaccines. In 1942, the CDC, known at the time as the Communicable Disease Center, was established and marked humble beginnings in Atlanta, Georgia. The next several decades held advancements in research, vaccines, and tracking efforts (which now take a look at the geography and population of those affected by the flu), including their flu activity tracking system which launched in 1962.

1940s – Flu Vaccine Trials

In 1940, the University of Michigan encouraged scientists to develop a flu vaccine with the support of the U.S. Army, due to the flu’s heavy impact on the military. Two years later, a two-component vaccine was developed to cover both influenza A and B strains. It was licensed in 1945, but found ineffective two years later when that year’s strain changed.5 It was during that same year that public health officials called for action and began regularly surveying the various flu viruses in an effort to stay ahead of future flu strains.

1960s – Vaccine Recommendations Made

In 1960, the U.S. Surgeon General recommended a since-updated flu vaccination for those with chronic illnesses, people age 65 and older, and pregnant women.

1970s – Swine Flu (H1N1) First Appeared

In the 1970s, an outbreak of a unique strain of flu first appeared – today known as swine flu or H1N1.Though it’s a strain that normally infects pigs, it can also infect humans, particularly if humans come into contact with infected pigs. It presented a unique challenge, since vaccines introduced up to this point were designed against human strains, not swine strains. There were also concerns about the strains coming into contact and creating a new virus – something the world would experience in 2009, which you’ll read about shortly.

2000s – Keeping the Public Informed

Fast forward to the 2000s, when the National Incident Management System (NIMS) was established to keep the public apprised of all public health matters, including flu pandemics. It was the first of many task forces, strategies, and associations formed to handle future flu concerns.

When a new strain of H1N1 was detected in the United States in 2009 (with bird, pig, and human genes), health officials became concerned about the potential of another pandemic. That same year, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the outbreak a pandemic (because it was a new virus that easily spread from person-to-person), which launched a “complex and multi-faceted response to the H1N1” that included public education, an aggressive approach to H1N1 prevention and vaccinations, and scientific research to help understand the new strain.3

Flu Fact: From April 12, 2009 to April 10, 2010, roughly 60.8 million people were diagnosed with the H1N1 virus.6

2010s – Vaccine Recommendations and Schedule Updates

In 2010, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended annual flu vaccines for those 6 months of age or older. Prior to this, flu vaccines were already added to regular vaccine schedules.

2017 – Updated Flu Guidelines by the CDC

The most recent development in flu occurred in 2017 when the CDC issued updated and simplified guidelines meant to encourage healthy habits, including covering coughs and sneezes, staying home when sick, and practicing good handwashing hygiene.

2018 – What to Expect

Now, as researchers continue to predict the upcoming year’s most common circulating flu strains, new discoveries are being made to keep flu vaccinations as effective as possible. For example, when it's sunny and mild here in the United States, places in the Southern Hemisphere, like Australia, are currently tackling the colds and flu of winter. Researchers can look at flu seasons in the Southern Hemisphere and use it to make predictions about the flu season in the United States. That's because, historically, flu seasons in the United States tend to mirror those in Australia. As of now, the 2018-2019 Australian flu season isn’t so bad, and officials with the World Health Organization are calling it “very mild.”7 This year, flu vaccines are prepped to combat the anticipated strain of flu. When they’re administered annually, the flu vaccine gives your body a chance to build antibodies so that it can ward off harmful germs.

Flu vaccines are available in our neighborhood medical centers across the country. With our convenient hours, we're here to help you stay healthy this flu season.

Originally published October 2018. Updated March 2024.

References:

1 CDC: History of 1918 Flu Pandemic. Last updated March 21, 2018. Accessed March 19, 2024.

2 CDC: Influenza Milestones. Last updated March 22, 2018. Accessed March 19, 2024.

3 NPR: 1918 Killer Flu Reconstructed. Last updated October 5, 2005. Accessed September 4, 2018.

4 CDC: What are Flu Antiviral Drugs. Last updated June 20, 2018. Accessed March 19, 2024.

5 CDC: Historic Timeline. Last updated May 3, 2018. Accessed March 19, 2024.

6 CDC: H1N1 Flu. Last updated June 24, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2018.

7 AARP: What Australia’s Flu Season Tells Us About Our Own. Last updated August 14, 2018. Accessed August 20, 2018.